Folders |

Fresh Kicks - The Rise of Noah Lyles And The Mom Who Helped Make It HappenPublished by

Fresh Kicks The rise of Noah Lyles, and the mom who helped it happen A Story By Dave Devine On a recent Sunday morning, exactly nine days after Noah Lyles blazed off the turn at the Doha IAAF Diamond League track meeting to win his first 200-meter race of the season in a personal-best 19.83 seconds, seven days before he’d headline the adidas Boost Boston Games as television announcers declared him a “scintillating young American talent at the age of 20,” the track star and social media enthusiast dropped a sweet, sentimental post on his Twitter account. Dear Mom Happy Mother’s Day. I truthfully would not be here if it wasn't for you and not because you gave birth to me. Even tho that is true. But because no one would work or believe as hard as you do. Hope you enjoy your gift…

The referenced gift was displayed in a photo accompanying the tweet. A pair of white adidas Superstars, iconic tri-stripe logo a flashy metallic gold, heels customized with hand-painted, matching gold roses. The shoes were a result of Lyles’ labors on the track, a product of his sponsorship with adidas. But the custom paint job — that was all Noah. Taken together, the tweet and the gift, the heartfelt message and the implied journey behind it, represent a complex intersection of talent and passion, effort and opportunity, gifts recognized and nurtured by Keisha Caine-Lyles. Humble beginnings and hard-earned outcomes. “Any time I stop and remember that I’m running as a professional for adidas,” Noah says, “and I’m living comfortably, it’s not just me. A lot of that is from my mom.” And it started at an early age.

* * * 1. Breath. Imagine the exhaustion. You’re a 6-year-old kid who hardly ever sleeps. When the coughing fits start, there’s no way to know when they’ll end. Doctors call it asthma, but it’s not like the asthma other kids have — sucking in air, handled with an inhaler — it’s an incessant cough that leaves you doubled over, stomach muscles ravaged and aching. When it hits, your breathing is reduced to intermittent gasps, punctuated by a hoarse, raspy bark. It keeps you from eating. Makes sleeping prone in a bed nearly impossible. You wake up in the middle of the night sometimes, rush to the hospital. These are some of Noah Lyles’ earliest memories. “Ever since I was four,” he says, “I remember going to the doctor — or to the hospital — in the middle of the night, because I couldn’t breathe.” The gasps for air, the sharp bark of the cough — it was a kind of soundtrack for his childhood. “I remember days when that’s all I would hear,” Noah says, “and my mom would come in and we’d have these long, long nights, because I couldn’t go to sleep.”

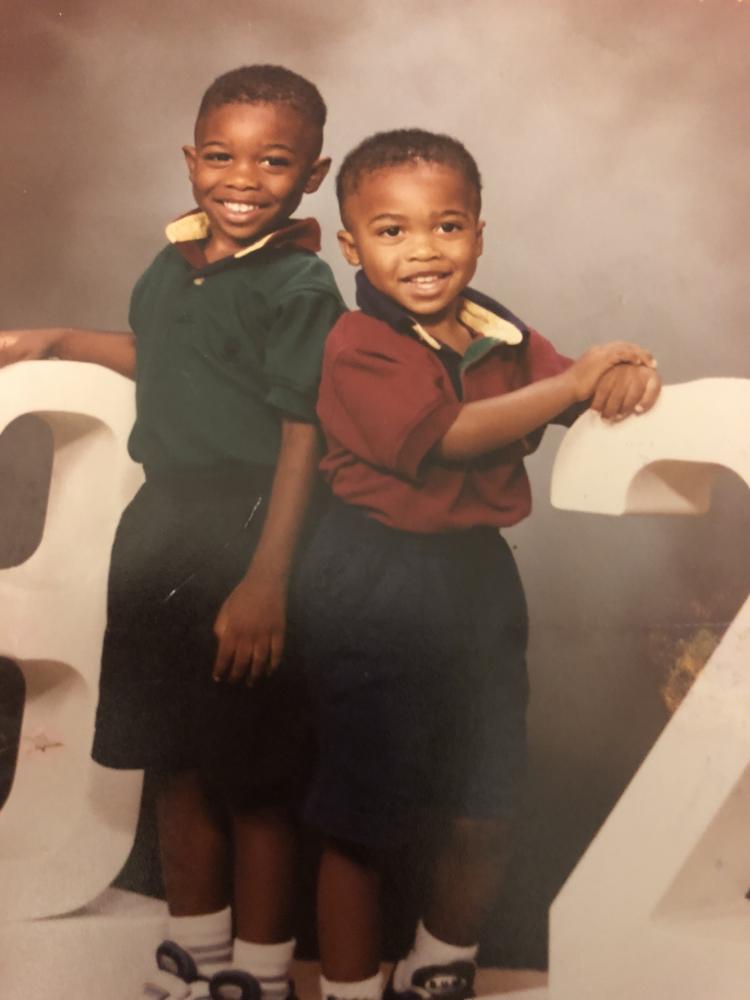

She’d wrap Noah in her arms, holding him upright because the cough occasionally subsided if he was seated, rub his back gently until he drifted into fitful sleep. “It was really, really tough,” Keisha says now. Sometimes the coughing was so persistent she’d rouse him and head to the hospital. He’d spend the night connected to a nebulizer, receiving breathing treatments and a raft of medications. Or the coughing wouldn’t be severe enough to warrant a midnight trip, so she’d simply spend the night supporting Noah into the small hours of morning, drifting in and out of consciousness herself, starting at the slightest movement. At the time, the family lived in Gainesville, Fla.; Keisha was homeschooling the boys. Noah was in first grade and Josephus, almost exactly a year younger, was in kindergarten. The sleepless nights made it difficult to rally for effective schooling some mornings. “He wasn’t sleeping,” Keisha says. “I was the teacher, and I was missing a lot of sleep...” When a state evaluator visited the house at the end of the year to assess the boys’ progress, Josephus passed without difficulty. Noah was judged to have met the requirements for completion of first grade, but just barely. Since he was already young for his grade and had missed so much instructional time with his debilitating cough, the Lyles’ decided to have Noah repeat first grade. That is how he and Josephus ended up in the same academic year, despite the age difference. A tonsillectomy when Noah was 7 seemed to diminish the frequency of the cough, and a combination of improved diet and involvement in a variety of sports helped to further reduce the effects. By second grade, the brothers had transitioned to a traditional public school. When their parents divorced around the time Noah and Josephus were in middle school, the boys moved with their mom and sister to northern Virginia, where Keisha had grown up as a child. There, the family faced new challenges. After initially moving into a house with Keisha’s brother, they transitioned through a series of homes while the family worked to stabilize in a city with a higher cost of living. According to Noah, the first school the boys attended in Virginia was “a rough setting,” a reality that left them transferring to Hammond Middle School, which fed into T.C. Williams High School. Even once they’d moved into their own apartment, Keisha struggled at times to make ends meet. “A few times we had our lights switched off,” Noah says. “Dinners — there wasn’t much variety for a while. We’d have a lot of leftovers. We saw how hard my mom was working.” Always, in the back of his mind, were those endless nights from early childhood — a tired mother supporting her son in bed so he could sleep. The concern they might return. It’s a foundational memory, he says, but one he’s admittedly reluctant to discuss these days. “Truth is, we’ve come so far from that.” PREFONTAINE CLASSIC TV/WEBCAST INFO NOAH LYLES, CHRISTIAN COLEMAN FACE OFF IN 200 AT PRE 2. Steps. Imagine the frustration. You’re a professional runner who can’t run, relegated to strolling laps on the same track you’re used to sprinting on. No telling stopwatch, no exploding from the blocks, no angling into the curves. Just the pedestrian cadence of your feet on rubberized oval. The grinding monotony of injury recovery. Every time you ask your coach for the day’s workout, the answer is the same: Outside lanes. Walk — not run. When Noah Lyles, not yet a year into a professional career that gleamed with promise, aggravated a sore hamstring in the first round of the 200-meter dash at the 2017 USATF Outdoor Championships — ending any possibility of advancing to the IAAF World Championships in London that August — this was his lot: rehab and healing at his training center in Clermont, Fla., watching his competitors race through the summer. Walking, while others ran. Keisha flew down to Florida to walk with him. “I just did laps on the track with him,” she says. “We’d walk and talk, and I’d try to lift his spirits.” Encouragement, in the form of accompaniment. She sold him on the idea that the temporary setback was character-building, that he needed to trust the recovery process, that he could come back stronger than ever. “When you become injured,” she says, “that’s when you do the most growing. Because you have the media and the cameras pulled away from you, and you see who you really are as a person. You have to be the one who still believes in you, when all the glitz and the glamour is gone.” Keisha and her former husband, Kevin, were both track athletes at Seton Hall University; Kevin competed professionally for adidas. She has experienced the cycle of injury and recovery firsthand, knows well the mental and emotional toll it can take on an elite athlete. She’s seen the highs and lows of track careers, the soaring expectations and shattering disappointments. It’s a knowledge base she’s had to access, in recent years, more often than she might have ever expected. Josephus was the first of her sons to push the idea of an early launch into a professional career, returning from Nike Elite camp the summer after 10th grade with the plan to become a pro immediately after graduation. “I was absolutely against it.” Keisha says, adding with a laugh that Josephus should be an attorney, because he’s an impressive debater. “But he was so adamant about it, I agreed to gather all the resources I could over the next couple of years in case the opportunity presented itself. So we could make an informed decision, rather than an emotional decision. That was my word, and I kept my word.” In her limited free time, around a career that saw her caring for adults with intellectual disabilities, Keisha began researching the steps involved in a transition to pro running. The elite meets to attend, teams to make, ways to attract the attention of agents and sponsors. “Me and my brother actually started worrying about her,” Noah says. “We were like, ‘You don’t have to really do this,’ because the only way we were going to make it to these track meets was that she’d have to pay for it out-of-pocket. She’d always say, ‘Let me worry about how we’ll pay for it, you guys just run.’” Noah and Josephus held up their end of the bargain, making U.S. youth and junior teams, setting national records, winning elite invitationals. Setting the prep track world on fire with a pair of decorated careers at T.C. Williams.

Mere weeks before the boys were scheduled to enroll at the University of Florida, where they would have joined an already-loaded Gators squad, the Lyles family shifted gears and began planning for a very different — and somewhat abrupt — transition to adulthood. “It was a last-minute scramble,” Keisha says, “that had been in the back of our heads for years. I just never expected it to come to fruition, even though I think they did. They always did.” While her sons moved through their initial year as professional athletes, Keisha — by necessity and request — continued many of the managerial responsibilities she’d assumed when they were teenagers in high school. Eventually, juggling the role of part-time manager and full-time social worker became too much. Keisha transitioned into a role the boys affectionately term: full-time “Momager.” “It took a lot of courage for me to step away from my job,” she allows. “I never thought it was going to happen, even though they always said that’s what they wanted me to do.” Some days, she might work with their CPA or serve as a liaison with Global Athletics and Marketing, the agency representing the Lyles brothers. Some days she’s conferring with wealth management and retirement teams. Or developing a charitable giving plan. Some days she pays bills, assists with nutrition planning and travel arrangements. Some days, she flies to Florida and walks on a track. When Noah initially aggravated the hamstring injury that found him rehabbing in Clermont, he was huddled afterward in the athlete warm-up area of the USATF Championship stadium in Sacramento, distraught at losing his chance to compete for a spot in London. Keisha found him there, along with Josephus, and convinced her sons to depart with her. “I said, ‘Okay, Noah, we’re going to walk out of this warm-up area as a team. We win together, and we’re going to walk out of here together, because I don’t ever want you to feel like you’re in this by yourself.” On the track, the 200-meter semifinals were about to begin. Without Noah. “We got our stuff, and we walked out with our heads held high, and I’m like — this is us. At the end of the day, if you’re going to have a track career, this is what counts — family. And the people who love you.” Two months later, a fully-recovered Noah stormed to victory from Lane 9 in the IAAF Diamond League 200-meter final in Brussels, Belgium, his 20.00 win redeeming a season that seemed lost only weeks earlier. More recently, Josephus has rebounded from his own spate of injuries, running personal bests over 200 and 400 meters. “When you get older,” Keisha says, “because you’ve overcome that adversity when you were younger, it makes you so much stronger. And it gives you so much more empathy for people who really are going through hard times in life.”

3. Kicks. Imagine the joy. You’re a kid who grew up with two main passions: art and athletics. Even when you were sick, hooked up to a breathing machine, or when schoolwork became too difficult or distracting, you had your sketchpad. The margins of your notebooks. You could lose yourself there, spend hours doodling and drawing. And when you realized, sometime in high school, that a shoe might be just another canvas, you embraced that, too. Customizing sneakers for yourself and your friends, hand painting the outsoles and uppers, tagging the tongues, making them unique, individual — all yours. Gradually discovering a sneakerhead subculture you barely knew existed. And now here you are, athlete and artist, stepping into the headquarters of a massive athletics apparel company — the one that pays you to run — spending a magical day shadowing designers, peeping concept art, taking a seat at the drafting table. You’re like Charlie in the Chocolate Factory, only this isn’t candy, it’s laboratory for shoes, and the lab smells like fresh kicks. Located in Portland, Ore., just before a neighborhood of leafy side streets surrenders to a gritty industrial sector, adidas’ North American headquarters is a gleaming complex of interconnected buildings, a former hospital transformed into a state-of-the-art corporate facility. A mix of commercial, creative and athletic space, with a busy employee store in the back, soaring workout facilities up front, and office windows peering into cluttered workstations, it’s like a playground for sneakerheads. There’s even an enormous pair of adidas shoes — vintage white Superstars — on a street-level pavilion, the sort of breezy, oversized installation begging tourists to pause for a selfie.

He spent time conferring with a color designer who explained the craft, let him try his hand at customizing a pair of unreleased, all-white Ultra Boosts. Sent him back to Florida with several more to practice at home. “I had a long talk with her,” Noah says, “while we were painting on my shoes, and I definitely would love to be brought in on stuff like that.” He doesn’t mean simply choosing colors, he means the entire process. “I’d love to be someone who has a pretty strong input on [shoe design], or even does that after I’m done running.” Long before he found track as a middle schooler, Noah discovered drawing as a way to keep occupied during those long stretches of sickness and frailty. “When I was sick,” he says, “I’d draw, because I couldn’t really do too much else.” Even on the days he wasn’t listless from the asthma, Keisha notes, he showed an easy distractibility in school, a directionless energy outside the classroom. Sometimes she’d find him climbing shelves during shopping trips to Costco or sprinting up playground sliding boards while other children were gliding down. “I noticed that whenever he’d draw something, it would calm him down,” she says. “So, when I noticed he had this gift for art, I wanted to do everything I could to help cultivate that gift.” The shoe customization started in high school, when a friend showed him a photo of modified Timberland boots, or ‘Timbs.’ “I went, ‘Those’re nice — bet I could do that, though.” He started making sketches, “things I wanted to do to them, and then I was like — okay, now I actually need a pair of Timbs.” He requested a pair for Christmas, keenly aware of the cost, then immediately started painting them with a University of Florida theme, the school he and Josephus were expecting to attend. “From there,” he says, “people started asking me to design things for them, so I decided to keep going with it.” When he signed with adidas, the company started sending him, as he says, “a lot of shoes. And you know, to be honest, some of those shoes I just don’t — ” Here he pauses a moment, chuckling over how to articulate this: “ — wear. So, I decided to give myself a reason to start wearing them.” He continued practicing, got better — just like running — and this past January purchased his first airbrush, planning to experiment with more professional fades, smoother color blends. “I always wanted to get into airbrush,” he says, “but you know…airbrush kits are expensive.” He laughs again, amused at how far he’s come. “I definitely didn’t have one in high school.” When Noah unveiled those custom white and gold adidas sneaks for his mom on Mother’s Day, it was an acknowledgement, not only of his love, but his appreciation for the distance the family has traveled. “I legit would not be here,” he says, “doing half the things I’m doing. I still draw confidence from her.” For Keisha, the shoes represented not only Noah’s artistic gifts, but his ability to extend those gifts toward generosity. “I love the fact that Noah created the shoes for me,” she says, “because when I wear them, it’s not just that he made them, but he’s using his gift to give me something. He’s always loved art…” So much so, it’s an early frontrunner for his second act once the sprinting career concludes. “If I can keep the artistic flow going when I’m done with track,” Noah says, “I would love for that to be the next chapter of my life.” For now, he’s very much living the current one. With precocious track talent and charisma to spare, engaging approachability and boisterous creativity, he’s routinely tagged as one of the future — and current — stars of the sport.

He exists, with seeming effortless facility, at an intoxicating intersection of track success and pop culture. A social-media-sweet-spot in which televised 200-meter victories flow smoothly into Fortnite-inspired celebration dances, in which Dragon Ball Z references are slipped seamlessly into post-race interviews. He donned R2-D2 socks for the Doha Diamond League meet, a nod to the event occurring on May 4th (May the Fourth Be with You). He dropped a freestyle rap with fellow adidas pro Sharika Nelvis in a promo video a week before the adidas Boost Boston Games, then nimbly deflected any criticism with a self-deprecating hashtag: #butimnotarapper. An impressive balance of light-hearted and laser-focused. Concentration and connection. At the recent adidas Boost Boston Games, after serving as the headline athlete in the marquee event — the 150-meter dash, after purring past Great Britain’s Nethaneel Mitchell-Blake in the final meters for a 14.77 meet record, after television announcer Ato Boldon proclaimed him the future of U.S. sprinting, noting that when the 2020 Olympic Games arrive, “if he’s healthy, he’s gonna be on that team,” and after the long-threatening rain finally began to fall, Noah was approached by two beaming children — the sons of his agent, Mark Wetmore. Squatting to their level, eye-to-eye with his young fans, he offered an exuberant hug which they shyly declined. Almost tumbling backward with amusement, he extended, instead, a pair of gentlemanly handshakes and challenged them to a “race.” Three kids, and several city blocks-worth of elevated blue track at their disposal. And so, as the NBC Sports telecast drew to a close, as the cameras turned away and the credits rolled, there was Noah Lyles, sprinter on the rise, setting off down that track, racing two giggling children into the rain. It is, as his mother says, what happens when the camera’s not on you that matters most. More news |

Noah’s mother spent countless evenings in bed with her little boy, shoe-horned into a bunk bed as her other son, Josephus, slumbered nearby. Sometimes her daughter, Abby, would climb in, too.

Noah’s mother spent countless evenings in bed with her little boy, shoe-horned into a bunk bed as her other son, Josephus, slumbered nearby. Sometimes her daughter, Abby, would climb in, too. Shortly after Noah placed fourth in the 200 at the 2016 U.S. Olympic Trials, breaking a 31-year-old high school record in the process, he and Josephus — injured at the time — were offered eight-year professional contracts with adidas, and decided to turn pro.

Shortly after Noah placed fourth in the 200 at the 2016 U.S. Olympic Trials, breaking a 31-year-old high school record in the process, he and Josephus — injured at the time — were offered eight-year professional contracts with adidas, and decided to turn pro. Noah certainly wasn’t a tourist when he visited the complex shortly after signing his professional contract, but he was filled with similar wide-eyed joy and fascination.

Noah certainly wasn’t a tourist when he visited the complex shortly after signing his professional contract, but he was filled with similar wide-eyed joy and fascination.